African Cuisine in America

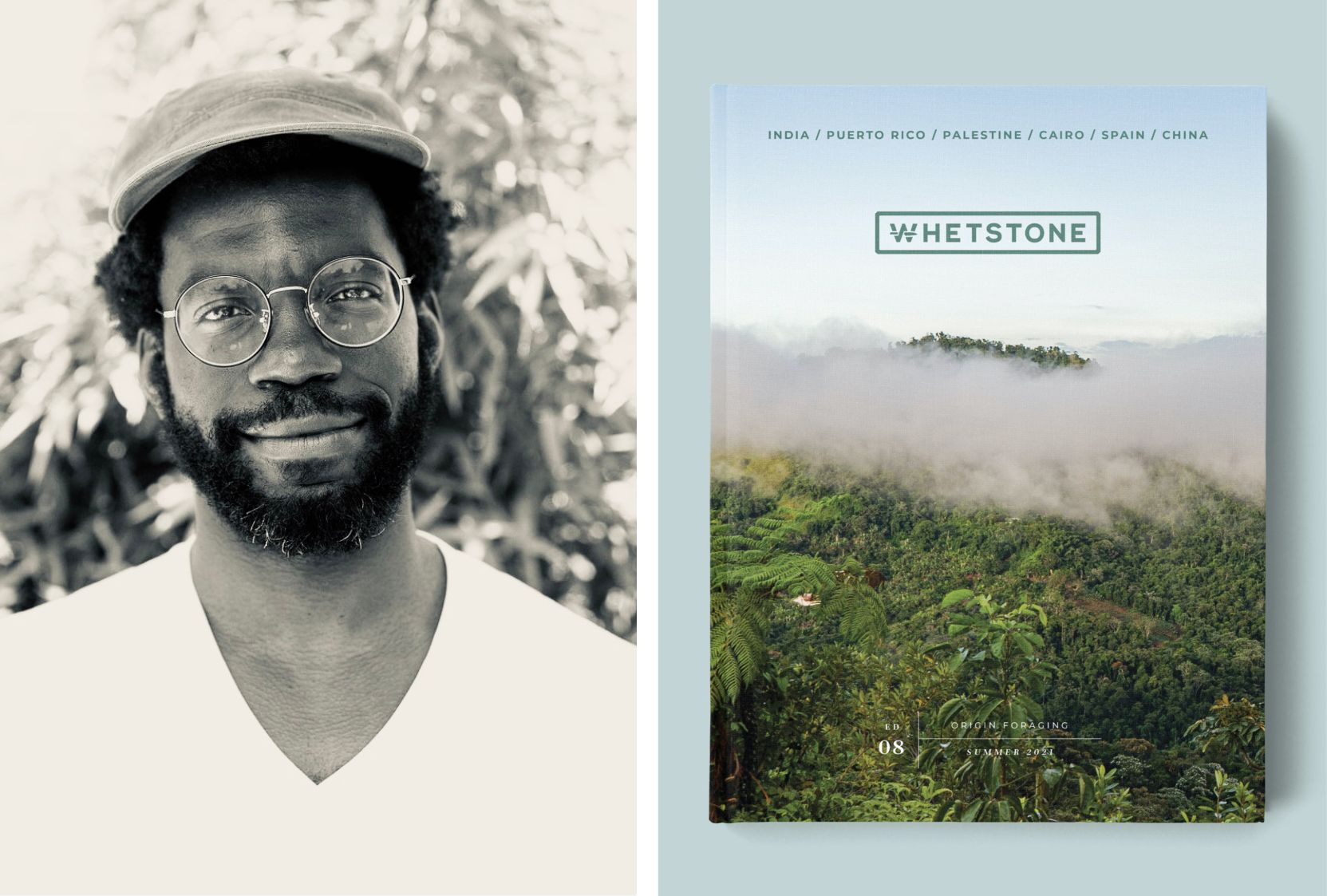

African-American food writer and media producer Stephen Satterfield redefines food as a means of better understanding humans and the world. As the founder of “Whetstone” magazine and the host of the well-acclaimed Netflix docu-series “High on the Hog: How African Cuisine Transformed America”, he is putting the missing piece on the puzzle of foodways connecting the United States back to Africa.

You are publishing an amazing magazine called “Whetstone” covering in-depth stories about food origins from around the world. When did you realize that eating was a political act?

Oh, well, good question. I think I realized it pretty early in my career, where I started studying in culinary school as a teenager. Food was always part of my life. And I think I was very lucky in that my culinary training was in Portland, Oregon. If any of your followers aren’t familiar with the geographies of the U.S., the West Coast is very well known for progressive thinking around organic food, local food communities and ecosystems since the early 1970s -the Bay Area and Portland in particular. I guess the first time I really started to think about food politics and the importance of supporting local food economies was probably in that vein. That was in 2004. Throughout that journey, I got increasingly more into the idea of food politics and particularly from a global point of view, understanding the connection not just between our local food systems, but industrial food systems and multinational food corporations. I wasn’t able to “unsee” the universal problems as well as universal histories and how much we can learn about one another, about ourselves, and our place in the world through food, as the primary means of exploration. I think that’s really what Whetstone represents.

What does “foodways” mean? I’ve been hearing this terminology in your talks a lot.

I don’t know what the formal definition is, but in our context, it’s essentially approaching food with an intersectional way of thinking. Most of the food reporting that we have seen up until very recently in the States celebrated fine dining restaurants with European-trained chefs and more specifically, French-trained chefs. So we ended up with a situation in which our dialogue around food was quite limited, and it was through almost exclusively a gastronomic or a culinary point of view. The perspective of “foodways” allows us to think about food from a more anthropological perspective. That includes the intersection of food culture, the people and the distinct migration stories -all those rich histories and fascinating intersections, as opposed to just thinking about food from a gastronomical aspect.

“The story begins in Africa and details the very gruesome Transatlantic Slave Trade that carried human cargo from Africa into the United States, and how these Africans who newly arrived on the North American continent began to make a way for themselves to change the society.”

THE MISSING LINK BETWEEN AFRICAN AND AMERICAN CUISINES

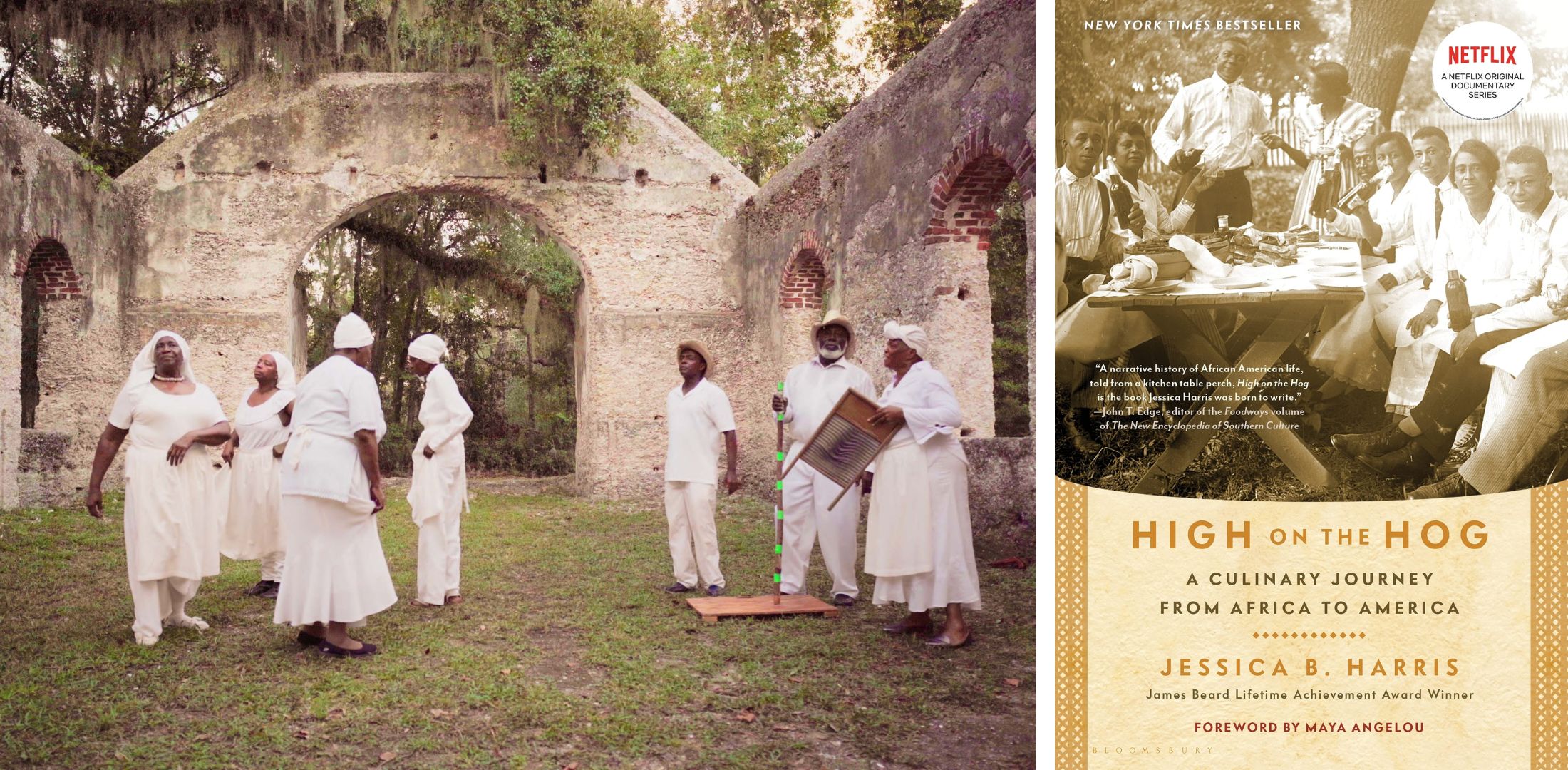

What you do for the latest recent mini-documentary series “High on the Hog” you host on Netflix seems no different. This documentary skillfully builds one of several missing links between Africa and Afro-American culture through food. Netflix had a hard time translating the title into Turkish, and they said something like “How Afro-American cuisine has transformed the USA”. What urged you to turn the book of culinary historian Jessica B. Harris into a mini-series?

Well, it wasn’t my idea. The book was acquired by two women who were the executive producers of the show and who have become dear friends of mine. Their names are Fabienne Toback and Karis Jagger. So, it was their vision. And I’m honestly just lucky that they included me in it.

What makes the film a universal one? How could people from other parts of the world resonate with it? You know, anyone from Turkey, Uruguay, or Thailand… The film’s context initially looks quite Afro-American, right? And then, it tells something to people from other parts of the world as well.

The book talks about the origins of African-American people through food as the medium. The story begins in Africa and details the very gruesome Transatlantic Slave Trade that carried human cargo from Africa into the United States, and how these Africans who newly arrived on the North American continent began to make a way for themselves to change the society. The book and the docu-series move chronologically to tell that story from Africa to South Carolina, and then throughout the United States, first up the Atlantic to the Northeast and then westward towards Texas, where we conclude the series. It’s like a snapshot of African diasporic history in the U.S. But actually, it is a story about human beings. And it is easy, I think, to relate to on the level of just being human. Food is really fascinating in this way, as it allows us to find our humanity in a way that is more accessible than anything. Because other than breathing, food is the only thing that we all must engage in. So food is a deeply human subject, and I think is fundamentally a migration story. No matter where you are from, somewhere in your history almost certainly has a connection to a migration story. I think that’s a big part of what people were attaching themselves to.

AFRICA: THE BLACK CONTINENT

As a member of the African diaspora in the U.S., was this documentary your first attempt to reconnect with Africa? Were you able to cross the distance of centuries and the ocean in between two continents in the end?

This wasn’t my first attempt to bridge with the motherland. Starting in 2007, I worked on a wine project in Stellenbosch in the Cape Winelands of South Africa, working with black vintners there. That was an extremely formative experience for me. Extremely! I just learned so much about the really difficult origins of the South African wine industry, how it was colonized and how the imperial presence of the English and the Dutch have dramatically altered that community in ways that continue to impact them even hundreds of years later, just like in the United States. We see the impact of colonization here too. I was fairly young then, in my early twenties, but it allowed me to begin to document these really complicated, lingering land-based issues. And that documentation taught me that food -wine in this case- has this unique ability to get to the point and make things plain that are otherwise hard to access. That was the beginning of my journey as a media maker. I was telling these stories from the Cape Winelands from 2007 to 2010.

In the first episode of the documentary, you visit Benin with Jessica B. Harris -the writer of the book. What is special about this little country? I am asking because the whole of Africa is still like a black or “obscure” continent for the majority of people living on the Earth.

You know, most of the Earth is anti-black and racist. So, part of that experience is about erasure and pervasive ignorance, which perpetuates racism. What ends up happening is people don’t think about Africa -not just people of European descent, but also including some black people who have adopted anti-black views in their own kind of colonial indoctrination. This is what we call “white supremacy” here in the U.S. Unsurprisingly, folks are ignorant about the African continent, even though it colors all of our histories. Certainly, all the colonial and imperial powers who have plundered the continent are quite familiar with it. When we lack curiosity about the African continent, it says more about our own racism than it does anything else.

So it’s also a learning process for black people, I guess. What were a few things that surprised you most in Africa during the shooting of the show? Did you have some revelation moments?

Yeah, there are so many things. Gosh, I’m trying to think of one thing. All of the many different expressions that were captured in the docu-series felt so familiar to me. It was not a huge surprise, but maybe a pleasant one, to know that whether we were in Texas, South Carolina, New York or Benin, there were certain ways of celebrating one another that felt uniquely black. As a member of the diaspora, it was really a pleasure to experience that kind of joy and convening and celebrating one another.

“You know, okra is originally from Africa and it has a kind of poor reputation here in the States, mostly because people aren’t super good at cooking it. But, when okra is prepared over dry heat so that it becomes crisp, it ends up as something that I really enjoy.”

AFRICAN CUISINE CELEBRATING LIFE

I would like to ask about your favorite African staples or dishes that you have discovered during your time in Africa. Can you think of any tastes that might be symbolically important?

I’ll just stick to the most symbolic ones. We cover okra in the first episode. You know, okra is originally from Africa and it has a kind of poor reputation here in the States, mostly because people aren’t super good at cooking it. But, when okra is prepared over dry heat so that it becomes crisp, it ends up as something that I really enjoy. Again, I like plantains.* We had many different varieties of plantains in Benin with different preparations. Cooked over a great open flame with coles, it was one of my favorite snacks that I had while we were there. Those are just two of the first and most symbolic kinds of snacks that come to mind.

Could you give an example of modern American food that carries the stamp of Africa?

We could talk about Hoppin’ John, which is a dish from the Gullah** people of South Carolina, who are descendants of West African people brought to South Carolina for their acumen as rice farmers. This is a dish made of field peas or cowpeas and rice. It usually has some kind of pork that is sauteed with onions and a small amount of seasoning and then added to the dish. So that’s one of my favorite expressions of an African-descended diasporic dish.

WHETSTONE: A MEDIA PLATFORM DEDICATED TO ‘FOODWAYS’

If we get back to the Whetstone… At that media platform, you have brought together a selected group of storytellers from around the world, focusing on food stories. What are some of the latest inspiring stories that you have covered in the mag?

It’s so hard to say, as we have so many. One of my favorite stories of late is in our print magazine Volume 8. One of our editors, who is an Ashkenazi Jew from New England, writes about the relationship between Jewish and Chinese food. These two are, again, diasporic communities, who kind of overlapped with each other in New York in the early 20th century. The ways in which these two communities cross paths with one another through food is a fascinating story. We also did a story about Haitian food in the same volume. We have done a coffee story about Puerto Rico, as well. So, yeah, I could go on. We are one of the most ambitious publications in the world when it comes to global foodways. Just this current edition has stories from India, Palestine, Egypt, and Spain. So it is really, really global in nature.

So, what’s next? How will you continue using stories to change the world?

Well, we will just continue to do it. I hope that it will continue to be well received. I think there’s so much ground to cover, so our work is unending. We have also started a new company in November and it will bring our global foodways to on-demand audio. So, we will have 10 new shows coming out under the umbrella of Whetstone Radio Collective, so listeners could stay tuned for that.

* “Plantain” is a type of banana with a very different flavor than the sweet, yellow banana that most of us are familiar. It is larger and tougher than a banana, and requires cooking, as it is not enjoyable to eat raw.

** Gullah people are known to have preserved much of their African linguistic and cultural heritage, due to their relative isolation from whites while working on large rice plantations in the States, covering thousands of acres in the coastal land of South Carolina.

To follow Stephen Satterfield and Whetstone on Instagram: @isawstephen, @whetstonemagazine

English

English